Game Theory and Design: The Stag Hunt

Share

Look, we've got opinions here at Vagrant Dog Productions. Lots of 'em. We won't subject you to all of them, but you can't stop us from talking about at least one subject: Game Theory, Game Design, and the occasional weird ways they combine.

Today, we'll be discussing The Stag Hunt and its role in cooperative games.

The Stag Hunt

We should specify; we aren't talking about the actual practice of stag hunting, nor are we referring to the centuries-old painting of the same name. Instead, we're talking about the risk-reward game of cooperation and assurance in game theory. The basic setup is as follows:

- A pair of hunters prepare to head into the woods. They can prepare for one of two hunts: a stag hunt or a rabbit hunt. They must choose which of the two animals to hunt before leaving on the hunt. Hunting a stag requires spears and dogs, while hunting a rabbit requires a few snares.

- The hunters prepare separately, and thus don't know in advance what the other hunter is preparing to hunt.

- Rabbits are easy to hunt and require little preparation. Should a hunter choose to hunt rabbits, they'll surely succeed. The downside? Rabbits are low-value food. Fun fact: in real life, it's possible to starve to death while eating rabbit (although it obviously takes a lot of time), a fate referred to as "rabbit starvation," since they provide protein but almost nothing else.

- Stags are swift, skittish, and can be up to twice the size of a hunter. Even with spears and dogs, a hunter can't hope to bring one down by themselves. This is a shame, because even after the extra costs, a stag is much better prey than a rabbit.

- Hunters are naturally cooperative. If a hunter encounters another hunter engaging in the same hunt, they'll help each other out. They'll then split the rewards of the hunt evenly.

- Most importantly, if both hunters decide to hunt for a stag, encounter each other, and work together, they're guaranteed a stag to split.

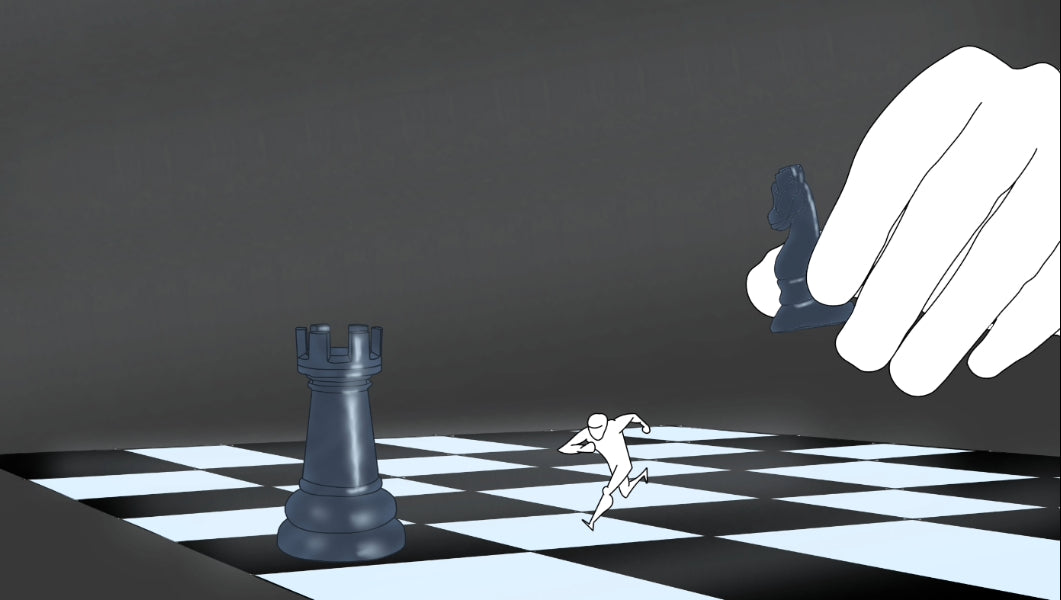

Before guns were an option, you didn't hunt stag alone.

This leads to an interesting situation, kind of like the opposite of a Prisoner's Dilemma. Three possible scenarios can play out as a result of this:

- Both hunters hunt for rabbits. They succeed and split the rabbits caught, ending up with slightly less than if they hunt alone.

- One hunter risks hunting for a stag while the other plays it safe and hunts for rabbits. The stag hunter, without assistance, fails, but the rabbit hunter not only catches some rabbits, but they don't have to share. Their catch is a bit bigger than in the first scenario.

- Both hunters risk hunting for a stag. They encounter each other, cooperate to bring down a stag, and end up with the best possible results for either of them.

Because of this setup, you would think that both hunters would go for the stag every time. However, that doesn't necessarily happen. Risk-averse hunters will play it safe and hunt rabbits, knowing that a guaranteed reward can be better than a bigger reward they might not get. A bird in the hand is worth two in the bush, and all that. Advanced versions of the Stag Hunt game will tweak the two possible rewards to see at what point the increased risk is worth it, or turn the game on its head (and thus into a variant of the Prisoner's Dilemma) by letting the hunters meet first, then decide what they will hunt. Will one hunter betray the other for guaranteed food?

The key to this particular game is that, up until each hunter makes their decision, there is no assurance that the hunters will act to mutual benefit. If the hunters knew in advance what the other would do, the two of them would hunt for the stag every time. Because they don't know that, however, each hunter has to make a choice: do they take care of themselves, or try to work together, knowing it could end in going hungry?

The Hazard of Cooperative Gameplay

The Stag Hunt isn't as well-known as the Prisoner's Dilemma, which aligns pretty well with another fact: competitive gameplay is more common than cooperative gameplay. Because of these two facts, most people playing games are inclined to be risk-averse when the opportunity to cooperate presents itself. Imagine a scenario similar to the Stag Hunt, but played out around a board game: two players are presented with a choice. If they both choose Option A, they win the game. Should they both choose Option B, they both score points, but it won't be enough to win. Should only one player choose Option A, that player gets nothing, but the player who chose Option B gets points regardless.

Unless the game is designed to encourage cooperative gameplay, most of the time, you'll see both players choose Option B. Even if they were okay with sharing a victory (and there's no guarantee that's true), they'll be hard-pressed to blindly trust another player in the moment, especially if they normally compete. This happens even if the two players can communicate with each other, because hey, words are cheap.

Let's say that you want to design a cooperative game. What's more, you want to design the game such that cooperation is a choice, not a requirement. Effectively, you want to encourage your players to be good to each other without forcing them to be on the same team. How would you do that?

Well, if you're familiar with the Stag Hunt, you'll have a couple of options.

Merging Game Theory and Game Design

Every time you design a game, you employ certain rules and mechanics to influence the resulting play. For ease of reference, we're going to refer to these rules and mechanics broadly as "levers." Should you decide to design your own game, just understand that when we say "pull this lever," what we mean is "add a rule or mechanic that causes the reaction we're talking about." Also, we'll continue to talk in terms of the Stag Hunt, but you should know that the strategies mentioned are meant to be universal in nature; take what you learn here and apply it to any game where a scenario similar to the Stag Hunt can occur.

Now, when it comes to designs that encourage cooperation, you have three levers you can pull, and one of those levers has a little toggle. We'll talk about that one first:

Reducing Risk. There are two broad ways you can reduce risk. The first is to lower the penalty for risking a stag hunt instead of a rabbit hunt. This can be done by increasing the number of hunters, but keeping the number of hunters needed to successfully hunt a stag below the total number of hunters. Without the need to get everyone to agree to the stag hunt, the perceived risk drops. You can also reduce the risk by granting the hunters who choose the stag a chance, however small, to take the stag themselves. You would be surprised at the rather drastic number of hunters who will try to hunt for a stag solo if they have a 5% of success, as opposed to those willing to try in the hope that the other hunt will help them.

The toggle mentioned above is the second way to reduce risk: you instead increase assurance. Providing a way to guarantee that the other hunter will join in the stag hunt will have the same effect as lowering the actual risk, by which we mean it will lower the perceived risk, which is the actual value affecting the behavior of the hunters. For example, if hunters opted into a stag hunt by adding their hunting resources to a public pool, other hunters could see who has opted in and respond accordingly. Considering they have more to gain by joining than by not, this assurance that at least one hunter will be engaging in a stag hunt will increase the odds that the other hunter will hunt for stag too.

Increasing Payoff. As it happens, if the rough odds that a hunter will choose a stag hunt over a rabbit hunt reach a tipping point when the reward for hunting the stag is about double the reward for hunting a rabbit, per hunter. For example, if your share of the stag was about ten times the meat you would gather while hunting rabbits (with or without another hunter), most people would consider themselves fools for not hunting a stag. If you only gained a few extra pounds, however, the Fear of Missing Out would drop noticeably.

When designing your game, take that into account. If you want to control how likely a group is to cooperate, change the relative value of the reward for cooperation versus working alone.

Increasing Inertia. Games that require decision-making have a certain inertia around those decisions. All else being equal, a player will tend to stick with a given decision unless doing so is likely to cost them, rather than reward them. To give you an idea of how this looks, let's say that we tweak the Stag Hunt, so there is a new rule: before preparing for the hunt, each hunter must tell the other which prey they intend to hunt. They wouldn't have to actually prepare for that hunt, just state that they were going to.

In this instance, we have three likely scenarios. In the first, each tells the other they are going to hunt a stag. Knowing that they stand to gain the most by doing as they said, the two hunters do indeed hunt a stag, and prosper thereby. In the second, each tells the other they are going to hunt rabbits. Receiving assurance that the other will not be hunting a stag, the hunters are convinced to hunt rabbits as planned. In the third scenario, one says they will hunt a stag, and the other says they will hunt rabbits. In that case, the very heavy odds are that the stag hunter will change their mind. The rabbit hunter loses nothing by sticking to his plan, while the stag hunter has just been assured they will gain nothing by sticking to theirs.

If you want to increase the chances of cooperation, one of the ways you can do so is by designing the game so that the opposite is true: the stag hunter loses nothing by sticking to their plan, while the rabbit hunter is incentivized to join the hunter. In other words, you want to weight the decisions more heavily in favor of stag hunts. Probably the easiest way to do this is to introduce penalties to the lone rabbit hunter. They don't have to be severe— as risk-averse as people are, they are even more averse to negative consequences. For example, say that there are three hunters instead of two. Only two are needed to hunt a stag, but a further wrinkle is added: a wolf stalks the woods and will steal the prey of any hunter who works alone. As with the third scenario above, one hunter states they will hunt a stag, while the others state they will hunt rabbits.

The odds are very good that when they encounter each other in the woods, all three will be hunting a stag.

Why is that? Because the wolf introduces a risk to the rabbit hunters that the stag hunter does not have. Should he hunt alone, the stag hunter will not have any prey regardless, so the wolf changes nothing for him. The rabbit hunters know this, and they know that the other rabbit hunter could change their mind, join the stag hunt, gain the increased reward... and, more importantly, the last remaining rabbit hunter will have their prey stolen. With these changes to the inertia of certain choices, you now have a design where either every hunter cooperates to hunt rabbits, or every hunter cooperates to hunt a stag.

Conclusion

Perhaps you're starting to see how valuable game theory is when considering game design. Not in the sense of deciding what color your playing pieces are- in the sense of deciding how your players approach your game, and what decisions they will likely make because of the choices you made in your design.

This will be an ongoing feature, but not a weekly feature. Instead, posts about Game Theory and Design will pop up as they're completed. If you'd like to know when the next post happens, shoot us a message! We're happy to notify you.