Worldbuilding Wednesdays: Design Philosophy

Share

Welcome to Worldbuilding Wednesdays! Every Wednesday, we spend what is probably far too much time walking through our worldbuilding process. In this week's post, we talk about the basics of design philosophy. In other words: what ideals are we going to cleave to as we work? What method are we going to use to do that work? And what, exactly, do we need our world to do?

What We Have So Far

We have a singular image, which you might not think is much, but actually tells us quite a bit. The image is of a truck bouncing down the road, towing a trailer that has a dragon hitched down. This image tells us:

- This world has elements of fantasy

- This world has elements of modernity

- The fantasy elements are not hidden; they are instead treated as commonplace

- Someone capable of subduing a dragon still needs to use a truck to transport it

Based on that, we can pinpoint the genre of our world with relative confidence. Horror and science fiction are unlikely. Urban fantasy tends to hide its fantastic elements behind an everyday facade. High fantasy doesn't need a truck, and low fantasy wouldn't treat a dragon as commonplace. Most likely, what we have is an example of the corollary to Clarke's Third Law.

Clarke's Third Law is named for Arthur C. Clarke, one of the grandfathers of modern speculative fiction. It is his most famous law, and states that "Any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic." We've already crossed that point in the real world, as evidenced by the large number of people reading this with the aid of a rock we taught to think by electrocuting it in a very precise fashion. The corollary to Clarke's Third Law is that, by applying that same level of logic, any sufficiently advanced magic is indistinguishable from technology.

While the other genres mentioned had a problem with at least one aspect of our inspirational image, at least one doesn't: science-fantasy, a world where all the technology runs on magic (or vice-versa). How could a dragon be commonplace enough that a single person could transport it, but the magic level is low enough that the same person needs a truck to do the transport? Simple: the magic level isn't low at all. That's a truck fueled by magic. It just looks like a truck, because, say it with us: Any sufficiently advanced magic is indistinguishable from technology.

We now have one aspect of our Design Philosophy: that set of goals and principles which will help us build our world moving forward. As with every other step in worldbuilding, you can expand or contract this step as much as you want to. For purposes of this series, we're going to concentrate on four aspects: the Genre, which we've just determined; the Approach, which we've touched on previously but will get some more detail; the Goal, which is to have a world where our Inspiration makes sense; and lastly, the Key Elements, those features that we want to ensure our world has regardless of whatever else we do.

Because those Key Elements are key, we should get them out of the way before we get much further. But first, let's make sure everyone knows what they're talking about.

Dictionary Time

When you're worldbuilding, your goal might not necessarily be a world, so let's establish a sense of scale real quick with some definitions.

Setting. The location(s) where your eventual story will take place. If you aren't interested in designing whole worlds and universes, you'll probably limit your worldbuilding to the setting of your story. The setting may be as small as a single room (it has been done, especially in Victorian horror stories) or as large as the omniverse, which may be a little ambitious if this is your first real effort in worldbuilding. For most, the setting is a singular geographic area, just large enough to contain the action.

World. The world as a whole, as well as its immediate surroundings if they impact the world in any significant fashion. For example, in a story set on Earth, the "world" would likely consist of Earth, the Moon, and the Sun.

Universe. The chunk of space in which your world sits. While we're using the world "universe," what we're really talking about is the entirety of the fiction that all uses the same worldbuilding design philosophy, settings, and worlds. For example, the Marvel Cinematic Universe technically consists of a singular universe in the Marvel multiverse. The DC Universe, despite its similarities and nearly identical locations, is a different universe because the rules that govern it differ from those of Marvel. Many universes are, in fact, smaller than the worlds they reside on... but most cover multiple worlds, and a couple cover multiple iterations of what a physicist would call the universe.

Multiverse. A set of multiple universes that all use the same worldbuilding design philosophy. We already mentioned the Marvel multiverse; DC also has a multiverse, and technically so does Wizards of the Coast, ever since they made the worlds of Magic: the Gathering accessible to characters from Dungeons & Dragons. Generally speaking, a singular person wouldn't be able to craft an entire multiverse by themselves; each author who designs a universe using the same rules as others is adding to that design philosophy's multiverse.

With that out of the way, we can talk about Key Elements.

Key Design Elements

We needed to talk about those definitions first because, if you decide to do multiple worldbuilding projects, each with a different world, but you want to use the same Key Elements every time? You're building a universe, not just a world. It's something to bear in mind when you come up with those Key Elements. Should you find a set of Key Elements that you like, they'll eventually become the signature feature of your universe. If you convince others to use the same Key Elements as yourself, depending on how closely they adhere to those elements, they could help fill out your universe or even develop it into a multiverse.

The idea of sharing Key Elements in worldbuilding, by the way, is at least as old as the stories of H.P. Lovecraft. While Lovecraft was the inventor of such eldritch horrors as Cthulhu, the majority of the Cthulhu Mythos (the name of the shared universe that uses Lovecraft's Key Elements) wasn't written by him, but by other authors who were convinced to add to his tales of madness and the unknowable.

Because of this, you should consider the Key Elements you want to use carefully. A good set of Key Elements can become your signature work. ...As can a bad set of Key Elements.

No pressure.

So what is a Key Element? Simply, anything you decide needs to be present in your world. If this is your first time worldbuilding, you can start with those elements that need to be in your world for your Inspiration to work. If, for example, your Inspiration is a really cool fight scene between a French musketeer and a clockwork dragon, you'll definitely need to have the existence of France, musketeers, and advanced clockwork as Key Elements. Our Inspiration featured magic indistinguishable from technology, so that will be one of our Key Elements.

To that, we're going to add some Key Elements that are, well, a signature of work by Vagrant Dog Productions. In general, we're known for two big things in our world design:

- The world design follows from real-world physics as much as possible.

- Except for the characters, the bigger the better.

Let's expand on those two elements briefly.

Real-World Physics. When we design our worlds, even our fantasy worlds, we treat those designs with a variant of Occam's Razor. The variant is as follows: "Unless otherwise noted, assume that everything works as it would in real life." For example, unless we specifically make a change to, say, the gravitational acceleration of a world we're building, we can safely assume that gravity works the same way that it does on Earth.

We do this for two big reasons. The first is that we've had the KISS mantra drummed into our heads ("Keep It Simple, Stupid!"), and this means that, unless we have a reason to change how something works, we can simply use how it would work in real life and call it a day. The second is that, if we do change something, we can use physics to decide how that change affects everything else. For example, if we did change how gravity works, we could use physics to calculate what else happens, from how big plants grow to the weather to how popular basketball is.

If that sounds complicated, don't worry. We'll actually change how gravity works for the world we're building and then use physics to show how that changes our world. That way, you'll know.

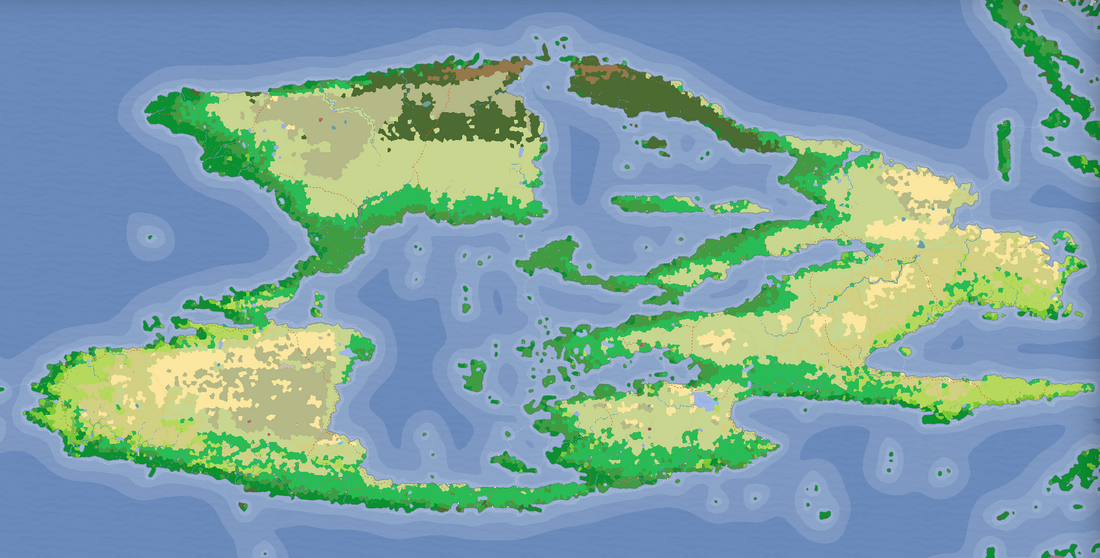

The Bigger the Better. They say a picture is worth a thousand words. Here are two thousand words' worth of our design philosophy.

Big trees are inherently cooler than little trees.

The only thing cooler than fighting big monsters is fighting big monsters by leaping through the air at them.

Conclusion

We said that we would address four aspects of the Design Philosophy guiding our worldbuilding: Genre, Goal, Key Elements, and Approach. So far, between this article and the article on Inspiration, we've at least touched on all four:

Genre: Science-Fantasy, where technology and magic mix freely.

Goal: We want a world where it would make sense for someone to drive casually down the road, towing a trussed-up monster with their truck.

Key Elements: Our world needs to adhere to the Genre; it needs to meet our Goal; it needs to default to real-world physics whenever we don't actively change something ourselves; and it needs to be a world where everything is big and people can leap through the air at monsters, because giant leap attack = cool.

Approach: Generally speaking, we're going to start from the Outside and work our way In, meaning that when we start to build, we'll address the largest parts of the world first. As we work, we'll get more and more detailed, until we're looking at specific characters.

Next time, we'll start the construction of the world by asking ourselves: how do we make the Key Elements true? Until next time, happy worldbuilding!